On a beautiful Sunday in April, when people were sunning themselves on a beach across the street, I was holed up in my home office, looking for Bruce Springsteen’s First Communion photo. I was writing about the rock star and determined to find that picture.

My reasons involved a quip I’d heard from an editor at a newspaper I worked for, which recently had run a series on organized crime.

“Have you noticed that whenever we do a story on a mobster, we run his First Communion picture next to the mug shot?” he asked.

My paper didn’t always run that photo — or place it next to the mug shot — but it did use it in a lot of profiles, obituaries, or other big-picture stories about a subject’s life. It wasn’t alone.

Newspapers, magazines, true-crime shows — all love First Communion photos. It’s a cliché, really, in journalism.

So why do the media keep using it?

The reason has nothing to do with religion. By journalistic tradition, an overview of someone’s life has pictures of its subject at varied ages. And the First Communion photo tends to be the best available childhood photo of someone raised Catholic: a good, clear, professional image.

In stories about people of other faiths, you’ll often see a secular counterpart: a photo of the subject in a Little League or Brownie or Cub Scout uniform (or in the case of Jim Morrison of the Doors, just the uniform, on display at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame).

All of us might like to think that our sterling words alone will cause editors to accept and readers to finish our stories, but it’s less and less true.

As publishing markets grow more competitive, every part of a story matters, especially what editors call “the art”: the photos, the illustrations, the graphics, or anything that adds visual interest to the text. Making the most of that reality can help you persuade editors to publish your story and people to read it when they do.

But every publication has its own ideas about what kind of art it likes. It also has its own rules for submission. Smaller publications may want you to send photos with your story and welcome those you took with your old iPhone 8. At larger media organizations, photo editors or art directors might prefer to buy stock photos or have a professional take them and to use yours only if they’re unique.

Either way — if you need to supply some or all of the art — countless books, articles, and videos can help. They’ll tell you how take a good photo, find out-of-copyright drawings, or create eye-catching graphics with Canva or another online tool.

What that flood tide of advice seldom tells you is why good art matters so much: It’s not just that it’s visually more attractive.

I spent years as a staff writer and editor for Glamour and a freelancer for other media that had great art directors or photo editors. At all of them, I saw how much difference the art could make in whether you could sell a story. Successful writers know that the words and pictures for a story go hand-in-hand, and they think about both.

Good art, I learned, can help you do five things that may boost your chances of making a sale or keeping readers hooked after you do.

Focus your ideas

Selling a story to editors and readers begins with having a clear focus for it, or knowing what you want to say.

You may have trouble finding a perfect piece of art if you’ve bitten off too much. You’re all over the map of your ideas and need to decide on your main point. Finding a photo you’d love to use can help: It may show you what you most want to write about in your story.

Make a good first impression

Every editor I know has rejected a story or query that made a poor first impression — with shaky grammar, the wrong tone, or a misspelled name.

The same can happen if you use an unappealing photo: one that’s dull, trite, or overfamiliar, even if the technical quality is high. Why should anyone expect your story to be fresh and interesting if your art isn’t?

Raise your story to a higher power

Good art is honest. It supports and complements your story — it doesn’t misrepresent what you’re saying.

It can also raise your story to a higher power. Filet mignon is filet mignon whether it’s served on Limoges china or a paper plate too flimsy to hold its juices, but an attractive presentation can add to the pleasure of eating it.

Say things you can’t

Stories are getting shorter everywhere, and good art can help to fill gaps.

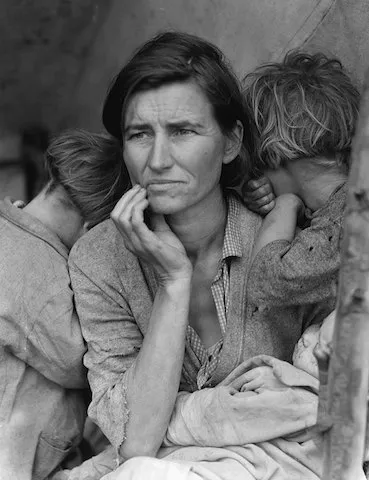

Some of the world’s most honored writers have written about the catastrophic Dust Bowl of the 1930s, including the Nobel laureate John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath. But it’s Dorothea Lange’s photograph, “Migrant Mother,” that for many people remains the defining image of that national tragedy.

Are Your Header Images ‘Exclamation Points’?

Splashy photos were a secret to the revival of a great magazine

Stop the scrolling

Every editor or art director likes a picture that “pops”: a visual exclamation point that stops you in your tracks. A famous example was a photo of a naked, pregnant Demi Moore that appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair in 1991. It was so popular — and widely imitated — the magazine later did a similar one of Venus Williams.

But a photo doesn’t need to have that kind of shock value to keep people from scrolling past it.

The great 19th-century photographer Frank Rinehart achieved that effect with haunting photos of Native Americans that defied stereotypes. One shows a San Carlos Navajo, identified only as Assuz. He’s beautifully groomed and dressed in what looks like a military uniform prominently adorned with a medal.

The photo of Assuz seems intended to honor him, but he looks unhappy, if not angry. Why? Did someone make him pose for that picture? If so, whom? You could look at that picture for hours, searching for an answer.

You may not always be able to find a piece of art that has that kind of impact. But in my experience, the effort pays off.

I could never find Bruce Springsteen’s First Communion photo, but my search led to the online Springsteen Archives at Monmouth University, a trove of other material. It had a class photo from St. Rose of Lima School in Freehold, New Jersey, taken at around the age at which the artist would have made his First Communion, and I ended up using that instead.

For my purposes, that picture may have been better, because it had more details, including a glimpse of Springsteen’s school and its uniforms. I can’t be sure, but I’d bet that the photo editor at my old paper would have liked it. He might even have admitted, grudgingly, that we’d run enough of those First Communion photos.